Practice

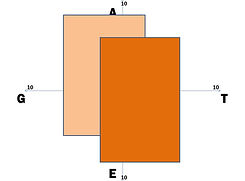

The GATE Model incorporates subjective measures of antecedents, on the axes of Genetics, Access, Trauma, and Environment, to create a graphic representation of the risk of addictive illness. The simple visual style of the GATE Model encourages involvement by all participants in treatment planning. Support systems are more likely to maintain their involvement, if they are given a clear view of the path to recovery from addictive illness, as the GATE Model engages significant others in realistic appraisals of client progress.

In the effort to find solutions for individuals suffering from addiction, clinicians are often left with constraints of time and resources that limit opportunities for securing the best treatment option. When innovative strategies succeed in carving through bureaucracy, resulting in positive outcomes for clients and their families, it may be in spite of formal agency policies. We may call it “intuition”, “clinical insight”, or a “hunch,” but when the sum total of clinical observations results in a novel approach with clients who are at risk for addictions, it is noteworthy.

Multiple treatment episodes become blurred, in the minds of clients seeking recovery from addiction, as motivation typically erodes over time. The GATE Model provides comparative views of sequential interventions, and their positive or negative impact on long-term recovery. In cases where clients have experienced chronic relapse, the GATE Model clarifies why past treatment may not have worked and targets specific area of a person's needs and resources, to optimize outcomes. The struggle to find a common language for communicating with clinicians, agencies, clients, and support systems can be daunting, among public, private, and paraprofessional resources. The GATE Model simplifies the negotiation of service options between diverse entities in the continuum of care.

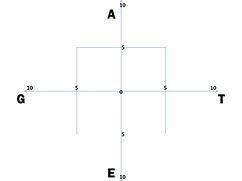

The GATE Model is a subjective measure of the risk of addictive illness, graphically represented along four axes:

• Genetics

• Access

• Trauma

• Environment

Each axis is measured on a 10-point scale, in increasing increments of risk of addiction. As a subjective measure of risk, the scaling of each axis of the GATE Model is a cumulative value of that axis, as estimated by the user, based on available information.

In practice, the scaling of each axis on the GATE Model depicts an observed level of risk, contributed by the Genetics, Access, Trauma, or Environment of the subject, as a value, on a scale of 0 to 10, based on observable features associated with elevated risk of addictive illness.

The user of the GATE Model considers information derived from subject interviews, collateral contacts, and treatment history, to derive an estimated risk value for each axis: Genetics, Access, Trauma, and Environment. The GATE Model does not replace evidence-based measures that are validated within structured addictions treatment protocols. Rather, it serves as a user-friendly resource for communicating clinical observations from a variety of sources. Like other time-tested brief assessment tools, such as the CAGE and the MAST, the GATE Model captures relevant information in an actionable, visual manner that informs and guides treatment planning.

Assessment

.jpg)

“Why?”

The well-groomed middle-aged man projects a desperate confusion that is all too familiar, to human service professionals working with addictions, as he expresses shock and dismay over a recent DWI arrest that is now threatening his carer. Our best efforts at explaining the etiology of addiction, however, bring this husband and father little consolation, as he asks the inevitable question that punctuates these emotional sessions: “Why…why did this happen to me and my family?”

Show and Tell

The GATE Model allows professionals to show their insights into the current risk of addiction and the potential outcome of treatment options, and not merely tell them to the stakeholders in clinical decisions. The visual impact of the GATE Model increases the accessibility of the clinician’s observations, strengthening the motivation of clients and families to accept recommended interventions. Patterns of addictive illness are familiar to professionals in treatment settings, who have witnessed different versions of the same dynamic, again and again, and the GATE Model captures the clinician’s unique view.

The utility of the GATE Model, as a brief, addiction-specific, subjective tool, lies in its applicability, across addictive agents and individual differences. Traditional concepts of addiction, with their one-dimensional approach, have missed the diversity of experience that is observed in actual assessment and treatment. Capturing the unique perspectives of the individual and their support system within the GATE Model empowers the professional with the perspective to implement the goals of person-centered planning, more effectively addressing that inevitable question…”Why?”

Worth a Thousand Words

Developed within the Masters of Social Work curriculum of the University of North Carolina, Wilmington’s School of Social Work, the GATE Model is an interactive, graphic tool that facilitates meaningful inquiry among educators and students, as they consider the deceptively complex etiology of addictions. In a climate of increasing budget restrictions for academic institutions, it has never been more important to target investments of time and resources strategically, over the traditional “one size fits all” approach to understanding addictions.

As a graphic representation of contributing factors, in the development of addictive illness, the GATE Model creates a comprehensive view of the volatile circumstances that are observed with clients. Changes in the progression of addiction may be gradual and cumulative, or sudden and dramatic, a dynamic process that is often obscured by simplistic, antiquated approaches.

The GATE Model allows educators and students to share clinical observations in classroom settings and remotely, using the innovative GATE Model Software and GATE Model App. Graphic representations of the dynamics of addiction facilitate meaningful dialogue among the participants in an academic setting, at all levels of education. A picture is, indeed, worth a thousand words.

Education

Planning

Person-Centered Planning

The need for more effective approaches to diagnosing and treating addictive illness is underscored, as one considers the enormous expenditure of funding, in research, prevention, education, treatment, interdiction, and incarceration, related to substance abuse and other addictive illness in the United States. “Drug abuse and addiction are a major burden to society; economic costs alone are estimated to exceed half a trillion dollars annually in the United States, including health, crime-related costs, and losses in productivity,” (Volkow, 2007).

In the current economic landscape of doing more work with fewer resources, the GATE Model helps achieve the goals of person-centered planning: identifying needs, allocating resources, and communicating priorities. National trends have increasingly utilized person-centered planning in the program-development of agencies, through tools that “provide ways to think through a situation before deciding what should happen next – making smarter decisions”

Tracking outcomes within a person-centered plan becomes more intuitive with the use of the GATE Model, because the comparative values for risk of addiction, over time, give a clear picture of positive or negative changes. This information can also be used to specify case management goals, suggesting a focus for the most significant risks, allowing providers to link clients to natural supports and community resources that can specifically address their needs.

Timely

Communication of needs and resources among agencies and stakeholders may easily get lost in the sheer volume of information conveyed. The GATE Model provides a graphic matrix that effectively transmits the salient points of program development goals.

Given the limited resources in the mental health service continuum, and the typically time-sensitive opportunities to assist individuals suffering from addictive illness, the GATE Model is a valuable tool for communicating priorities in program-development.

Multiple treatment episodes become blurred, in the minds of clients seeking recovery from addiction, as motivation typically erodes over time. The GATE Model provides comparative views of sequential interventions, and their positive or negative impact on long-term recovery. In cases where clients have experienced chronic relapse, the GATE Model clarifies why past treatment may not have worked and targets specific area of a person's needs and resources, to optimize outcomes. The struggle to find a common language for communication between clinicians, agencies, clients, and support systems can be daunting, among public, private, and paraprofessional resources. The GATE Model simplifies the negotiation of service options between diverse entities in the continuum of care.

Economic challenges, shared across the socioeconomic strata, have heightened the urgency of balancing the needs of competing stakeholders in the larger health care system. As an “umbrella, under which all planning for treatment…occurs,” the “Key Values” of person-centered planning “supports a fair and equitable distribution of system resources.” Addictive illness is particularly known to lead those in its grips on a circuitous path of relapse and recovery, with multiple treatment episodes the norm…obviously necessitating the judicious use of available treatment resources, which may be facilitated by the GATE Model.

Development